Editor’s Note: To mark the 25th anniversary of the first worst-to-team in baseball history, the following article is an excerpt, reprinted with the permission of author and Baseball Magazine contributing editor Dan Schlossberg, from The Sports Publishing book, due March 1, may be ordered now from amazon.com.

1991: Worst to First

Opening Day

Sanders, lf

Treadway, 2b

Gant, cf

Justice, rf

Bream, 1b

Pendleton, 3b

Heath, c

Belliard, ss

Smoltz, P

Best Hitter Terry Pendleton

Best Pitcher Tom Glavine

Best Newcomer Terry Pendleton

The Season

Before the 1991 season, they could have been called The Bad-News Braves. With three straight last-place finishes and not a single season on the sunny side of .500 since 1983, Fulton County Stadium resembled a morgue that General Sherman should have torched.

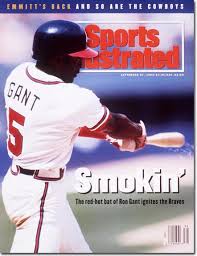

Sure, there were a few diamonds in the coal mine – Ron Gant made a successful conversion from infield to outfield while pulling off a rare 30/30 season, fellow slugger David Justice won Rookie of the Year honors after replacing long-time Atlanta icon Dale Murphy, catcher Greg Olson made the NL All-Star team in his first full season, and John Smoltz led the pitching staff with 14 wins despite a defense that led the major leagues in errors.

Determined to stop giving games away, new general manager John Schuerholz studied the free-agent list with his eye on players who knew what to do with a glove.

With the blessing of owner Ted Turner, who supplied the checkbook, and team president Stan Kasten, who wisely kept Bobby Cox as manager, Schuerholz scoured the market like a savvy shopper searching for dinner party ingredients.

His major acquisition was Terry Pendleton, a switch-hitting third baseman coming off a dismal season in St. Louis (.230 with six home runs). He also added Rafael Belliard, a shortstop whose pedigree precluded any help from his bat, and Sid Bream, a first baseman with strong defensive skills but hardly the type of hitter typically found at the gateway.

A veteran player on a young club, Pendleton relished the chance to be a team leader. He also appreciated the fresh start in Atlanta, where Fulton County Stadium would prove more friendly to his power – a factor that figured into his signing.

Pendleton not only supplied Gold Glove defense but hit for both power and average – silencing critics who claimed he was over the hill. He played hurt, starting everyy game after June 15 until the team clinched despite a cartilage tear in his left knee. In addition, Pendleton took it upon himself to counsel teammates with personal problems, including Brian Hunter and Keith Mitchell after both had alcohol-related automobile accidents that summer.

Although Bream came with surgically-repaired knees and a reputation as the slowest runner in the league, John Schuerholz found dazzling speed in two more new acquisitions: outfielders Otis Nixon and Deion Sanders. Both Nixon, acquired from Montreal in a spring training trade, and Sanders, a minor-league free agent who also played pro football, had never distinguished themselves at the plate. But the GM saw potential in both.

He also knew the defense would be vastly improved. It was not a half-vast judgement.

Buoyed by the knowledge that their infielders would turn grounders into outs, the young pitching staff developed by Bobby Cox during his tenure as general manager blossomed like the cherry trees in Washington. The team went from 65-97 in 1990 to 94-68 in 1991 – from 26 games behind to one game ahead.

It was the first time in the history of modern baseball that a team had finished with the worst record in the majors one year but finished first the next.

After lulling their followers to sleep with a slow start in April, the Braves hit their stride in May, winning 17 of 26. Justice was

National League Player of the Month while Tom Glavine, a lefthander just two years removed from a 7-17 campaign, was the NL Pitcher of the Month. En route to the first of five 20-win seasons, he went 6-0 with a 1.76 earned run average to earn the honor.

A June swoon, coupled with injuries to Justice (back) and Bream (knee), burst the Braves balloon as they limped the All-Star Game one game below .500 and 9½ games from the NL West lead. Since the players were still getting to know each other, the Braves may have needed the three-day break. Either that or they ate their spinach – something triggered a second-half explosion that started with a 9-2 mark after the break. Led by Nixon, Pendleton, and 21-year-old lefthander Steve Avery, Atlanta gained seven games on the front-running Los Angeles Dodgers in a 12-day span.

They never let up, going 55-28 after the All-Star break for a .663 winning percentage. Taking 21 of their last 29 (.724) helped.

Along the way, the Braves even got a combined no-hitter from Kent Mercker, Mark Wohlers, and Alejandro Pena, acquired on waivers in August to replace the injured Berenguer (stress fracture of the forearm). Pendleton hit a home run for the Atlanta run but backed away from an infield chopper with two outs in the ninth. When it bounced off Rafael Belliard’s glove, the crowd groaned, assuming it would be ruled an infield hit. But the official scorer, who doubled as a local sportswriter, charged an error instead. All Pena had to do was retire Tony Gwynn, the toughest out in the league. He did, coaxing a fly ball, and the National League’s first combined no-hitter was official.

That September 11 masterpiece was not the only surprise of the second half.

On August 21, Atlanta was one out away from a 9-6 defeat against Cincinnati when third-string catcher Francisco Cabrera turned a Rob Dibble fastball into a three-run homer with two outs in the last of the ninth. The Braves eventually won the game on a Justice double in the 13th.

Just five days later, the Braves parlayed a Justice homer and Jeff Blauser grand-slam into an 8-7 win over Montreal – after trailing early by a 7-1 margin.

Bream’s grand-slam on September 15 contributed to a big win over the Dodgers, giving the Braves a game-and-a-half lead, but the lead changed hands seven times in the final month.

Perhaps the biggest game of the nail-biting campaign came on October 1. The Reds led early, 6-0, but the lead had dwindled to 6-5 by the ninth. Enter Dibble, the fearsome fireballer who had been victimized by Cabrera six weeks earlier.

Though Justice would play only 109 games that season, his flair for the dramatic seemed almost routine by that point. An impatient hitter who often tinkered with his stance, he had all the moving parts going in the right direction that night. He connected with a man on to win the game, 7-6, and put the Braves one game back with four to play. A day later, a Braves win and Dodgers loss left the clubs tied.

Though Justice would play only 109 games that season, his flair for the dramatic seemed almost routine by that point. An impatient hitter who often tinkered with his stance, he had all the moving parts going in the right direction that night. He connected with a man on to win the game, 7-6, and put the Braves one game back with four to play. A day later, a Braves win and Dodgers loss left the clubs tied.

Avery’s win over the Houston Astros on October 4, coupled with a Dodgers defeat in San Francisco, put the Braves up by one with two left.

Then John Smoltz, capping a 12-2 second half after a 2-11 start, pitched the Braves to their eighth win in a row, clinching a tie. If the Giants could beat the Dodgers again, the title chase would be over. They did – as a packed house at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium watched the broadcast on the scoreboard.

Down the stretch, potent pitching plus timely hitting pushed Atlanta over the top.

One year after finishing with the worst earned run average in the majors (4.58), Braves pitchers posted a 3.49 mark, fanned a club-record 969 hitters, and held rivals to a league-best .240 batting average. Atlanta also proved stingy, yielding the fewest hits of any National League staff.

The front four starters all had fine seasons. Glavine tied for the NL lead in wins and complete games while finishing second in innings pitched and third in strikeouts. The first Braves pitcher to win 20 since Phil Niekro in 1979, Glavine capped his campaign by beating out future teammate Greg Maddux, then with the Chicago Cubs, for the Cy Young Award.

The stoic southpaw refused to admit he was superstitious but acted otherwise. He always took the same number of warmup pitches, sat in the same spot in the dugout, hung his jacket on the same hook, and took off his cap and put it back on his head three times when on the mound. During one game, he lost the gum he was chewing, grabbed it off the dugout floor, washed it off, and put it back in his mouth. Glavine was merely following the advice of Ralph Kiner, the Hall of Fame outfielder who always stepped over the white lines when running to his position. “I’m not superstitious,” he said, “but I didn’t want to take any chances.”

Fellow lefthanders Avery, third in the league in wins, and Charlie Leibrandt, the stablizier of an inexperienced staff, started 69 games and won 35 of them. Avery won his final five to become the youngest 18-game winner in Braves history. Smoltz also finished strong, winning eight of his last nine.

In the bullpen, Berenguer and Pena blew only one of a combined 28 save opportunities while the lefthanded Mike Stanton proved a durable and dependable set-up man. Mark Wohlers, who would blossom into a quality closer later, even worked in 17 games after making his major-league debut in 1991.

The team’s biggest surprise was the 30-year-old Pendleton, whose availability through free agency did not convince many suitors. He not only led the league with a .319 batting average but finished first in hits and total bases and third in slugging. He was rewarded after the season with the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award, Comeback Player of the Year honors, and a Gold Glove for fielding excellence. That made him the first Brave to win MVP honors since Dale Murphy won back-to-back trophies in 1982-83 and the first to win a batting title since Ralph Garr in 1974.

Bream and rookie Brian Hunter formed a left-right platoon at first base, contributing a combined 23 home runs, while Jeff Treadway hit .320 while sharing second with Mark Lemke and the versatile Blauser. Niether Belliard nor Olson managed to hit .250 but compensated with strong glovework.

Gant was third in home runs (32) and runs batted in (105), both tops on the club, and led the majors with 21 game-winning hits. In completing his second straight 30-30 season, he joined Willie Mays and Bobby Bonds as the only players at that time to turn the trick two years in a row.

Nixon, like Gant and Sanders, added considerable speed to the lineup. Thanks to a career-best .297 average that allowed him to reach base often, he swiped a club-record 72 bases, second in the circuit, before he was suspended September 16 for substance abuse. He had failed a drug test in July but was allowed to continue playing after he and agent Joe Sroba contested the results. Nixon’s absence was felt most keenly in the postseason – especially since Lonnie Smith served as his primary replacement.

The Postseason

To reach the World Series for the first time since 1958, the Braves had to beat the power-packed Pittsburgh Pirates in a best-of-seven playoff. Although the more experienced Pirates were favored, pundits hadn’t factored in the enormous potential of Atlanta’s young pitching.

Pittsburgh had led the league in batting and runs scored during the season but that didn’t matter to Atlanta pitchers.

Steve Avery not only took the second and sixth games by 1-0 scores but worked 16 1/3 straight scoreless innings, a National League Championship Series record, to win Most Valuable Player honors. John Smoltz clinched the flag with a 4-0 shutout in the seventh game.

Atlanta pitching was impregnable. It posted a composite 1.57 earned run average while holding the heavy-hitting Pirates hostage for the last 22 innings of the entire series. Nor did Pittsburgh score a run at home in its last 27 innings at home.

Pittsburgh won the opener at home, 5-1, but Avery combined with Alejandro Pena for a 1-0 shutout in the second game. The Pirates then won consecutive squeakers, 3-2 in 10 innings and 1-0, after the series reverted to Atlanta. That meant the Braves had to win both games in Pittsburgh to win the pennant.

They not only won but held the heavy-hitting Pirates scoreless. Avery and Pena combined for another 1-0 win on October 16 and Smoltz, buoyed by a three-run first, banked the Bucs with a six-hit complete game the next day. Pena, who had converted all 11 of his save chances after his August arrival from the Mets, saved both of Avery’s wins and added another save in the World Series that followed.

The Braves had lots of other heroes, including a few surprises.

One year after becoming the first Braves rookie to make the All-Star squad, 30-year-old catcher Greg Olson became a

surprise hitting hero when it counted most. His .333 NLCS batting average tied Brian Hunter for best on the Braves and he even hit a rare two-run homer in the third game. Hunter, Sid Bream, Ron Gant, and David Justice also homered in the seven-game series while Gant and Justice shared the team lead with four runs scored (Gant’s seven stolen bases, an NLCS record, helped).

MVP honors went to Avery, a 21-year-old lefthander who had won 18 regular-season games, two of them during the pressure-packed final month. Nicknamed “Poison” Avery by Pirates outfielder Andy Van Slyke, he became the youngest pitcher ever to win a playoff game. He fanned 17 men in 16 1/3 innings while posting a perfect 2-0 mark and 0.00 ERA against Pittsburgh.

The 1991 NLCS was the first postseason series to feature three 1-0 games. But that score would resurface in the next round.

The World Series pitted two worst-to-first teams with the Braves against the Minnesota Twins.

Each team won all of its home games, thanks in part to partisan crowds whose decibel levels were amplified by the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome.

As John Schuerholz said later, the Braves were the champions of the outdoors while the Twins were the indoor champions.

In one of the most exciting Fall Classics in baseball history, five of the seven games were one-run affairs, four were decided on the final pitch, and three of those four extended into extra innings – a Fall Classic first. The series remained deadlocked through nine innings of the seventh game, eventually won by the Twins, 1-0.

Playing at home, Minnesota won the first game, 5-2, and led the second, 2-1, in the top of the third when controversy raised its ugly head. After Lonnie Smith was safe on an error by third baseman Scott Leius, Ron Gant singled to left. Seeing Dan Gladden’s throw get by Leius, Gant rounded first with second base in his sights. But pitcher Kevin Tapani retrieved the ball and fired a strike to first baseman Kent Hrbek. As the 170-pound Gant lunged for the bag, the 250-pound Hrbek appeared to lift his leg off the bag. Although Gant claimed interference, umpire Drew Coble called him out, ending the inning and killing a rally in a game the Twins eventually won by one run, 3-2, when Leius redeemed himself with a solo home run in the eighth inning against Tom Glavine.

Atlanta needed six pitchers and home runs from Justice and Smith to win a 12-inning duel in Game 3, a 5-4 affair played in Atlanta on October 22. Smith and Pendleton pounded solo homers the next night but the biggest hit was a ninth-inning triple by Mark Lemke, who came home with the lead run in a 3-2 game.

Smith, Justice, and Brian Hunter cleared the Fulton County fences in the fifth game, a 14-5 blowout in which the Braves scored a combined nine runs in the seventh and eighth innings.

Back in Minnesota, the Twins tallied two in the first against Avery and never trailed. It took 11 innings but the home team prevailed on a Kirby Puckett poke against veteran lefthander Charlie Leibrandt, making a rare relief appearance. Puckett, whose circus catch above the wall in the third nullified two Atlanta runs, was the only man Leibrandt faced.

That set the stage for a Game 7 showdown that pitted Smoltz against Morris.

After becoming the first National Leaguer to homer in three straight World Series games, Smith made a base-running gaffe in the eighth inning of the last game that denied the Braves their best chance to score.

Smith, who played for three different world championship teams, was quick on the bases and in the outfield. But he lacked good judgement, both on the bases and in the field, where he acquired the unflattering nickname of “Skates” for the way he glided after balls hit his way.

That judgement was evident even earlier than the 1991 finale. Smith had been thrown out at home in the fifth inning of Game 4, keeping the score tied at 1-1, when he couldn’t score from second on a double by Terry Pendleton. Only when the ball got past centerfielder Kirby Puckett did Smith start his run from second base to home. Puckett threw a strike to Brian Harper and Smith was out. Fortunately for him, the Braves rallied to win.

He wasn’t so lucky in the seventh game, however.

On first base with a leadoff single, he headed for second as Jack Morris threw the next pitch. Pendleton belted it to left-center but Smith, running with his head down, saw neither the ball nor the third-base coach. Noticing the runner’s confusion, second baseman Chuck Knoblauch deked the runner by pretending to feed the ball to shortstop Greg Gagne as if he were making a double-play. The ruse worked as Smith, who could have scored easily, stopped at second.

By the time he realized the Twins were still tracking down the ball, he could only advance to third. With runners on second and third and nobody out, the scoreless tie seemed to be on life support. By bringing in their infield, Minnesota needed a grounder to hold the runner at third and erase the batter at first. Fleet Ron Gant, coming off his second straight 30/30 season, obliged, with Smith holding at third.

David Justice, a dangerous lefthanded hitter, drew an intentional walk, setting up a double-play possibility that could end the inning. Sid Bream, a lumbering runner easy to double on any grounder, delivered just that – preserving the deadlock. The play went first-to-catcher-to-first.

“I made the mistake of not looking in,” said the 36-year-old Smith, who had previously played for three World Series teams. “I heard the crack of the bat and saw Knoblauch make a fake. Then I saw Dan Gladden move. By the time I got to second, I had to slow down to see if Gladden or Kirby (Puckett) could catch the ball. By the time I saw they weren’t going to catch it, I started running toward third but (third base coach) Jimy Williams held me up.”

Things could have been different if Otis Nixon had not been suspended for substance abuse in September. He had stolen a club-record 72 bases in the first five months and made a habit (double meaning intended) of driving rival pitchers to distraction. The Braves also missed the speed of Deion Sanders, who was spending the team’s unexpected postseason playing football for the Atlanta Falcons.

Nixon never got a chance to veto the Twins, allowing Lonnie Smith to fill his position. As a result, the Braves got more power but also more problems.

As a reward for escaping the eighth-inning jam, Minnesota manager Tom Kelly allowed Morris to stay in the game. In a Twins uniform for the last time, Morris meandered on into overtime.

John Smoltz worked into the eighth for the Braves but yielded to Mike Stanton in the eighth and Alejandro Pena in the ninth.

![John Smoltz and author Dan Schlossberg at the 2014 Winter Meetings in San Diego [photo by Perry Barber]](https://baseballmagazine.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/smoltz-and-schlossberg.jpg?w=300&h=169)

John Smoltz and author Dan Schlossberg at the 2014 Winter Meetings in San Diego [photo by Perry Barber]

The hero for the Braves in the 1991 World Series turned out to be little second baseman Mark Lemke, not known for his speed or his bat. A .234 hitter during the regular season, he singled in the winning run in Game 3, scored the game-winner in Game 4, and wound up with a .417 batting average that included three triples, tying a World Series record. His slugging percentage was .708. Not bad for a guy who couldn’t run.

Morris won the MVP honors that otherwise would have gone to Lemke. To compound the felony, the righthanded workhorse also positioned himself to haunt the Braves again a year later when he joined the Toronto Blue Jays as a free agent.

The young Braves missed stepping on the summit by only a step. Owner Ted Turner, taking the podium in the clubhouse after the last game, had a message for his team. “I told them I was real proud of them, no matter how the game came out, and I looked forward to seeing them next spring.”

He wouldn’t have to wait that long: the city saluted their heroes with a ticker-tape parade that snaked down Peachtree Street on October 29, 1991. Police estimated the frenzied crowd at 750,000 – almost as many people as the Bad-News Braves of the ‘70s and ‘80s would draw in a season.

MARTA, the city’s sleek subway system, reported triple its normal weekday ridership. The procession stretched for 12 blocks in a virtual sea of fans waving tomahawks and chanting. “I could hardly image what would happen if we’d won the World Series,” mused batting coach Clarence Jones.

Braves mania went viral. A woman wearing a Braves shirt in the New York Marathon was greeted by chants and cheers in all five boroughs. As far away as Japan, sporting goods stores were besieged by requests for foam-rubber tomahawks.

Although Atlanta missed a world championship by a whisker, the winter awards season was sweet. In addition to Pendleton’s MVP trophy and Glavine’s Cy Young, Bobby Cox was named Manager of the Year and John Schuerholz Executive of the Year. The team they built was young, talented, and capable of winning many more accolades in the years to come.